Guide to Genetic Screening

Emerging technologies over the last 25 years have afforded couples the option of being able to screen pregnancies for a variety of conditions. Prior to the emergence of screening, complicated pregnancies were often undiscovered until full term. The goal of all prenatal screening is to provide the expecting couple with as much information as possible, in an effort to optimize pregnancy outcomes. An unfortunate side effect of this type of screening is anxiety. It is very important to remember that almost all pregnancies are healthy ones.

There is a small minority of pregnancies in which there are problems with the egg or sperm prior to fertilization, or problems with the developing embryo or placenta. Looking for these pregnancies is the focus of prenatal screening and testing. Some of the problems which may be detected include:

Genetic Disorders

Birth Defects

Placental Disorders

Genetic Disorders

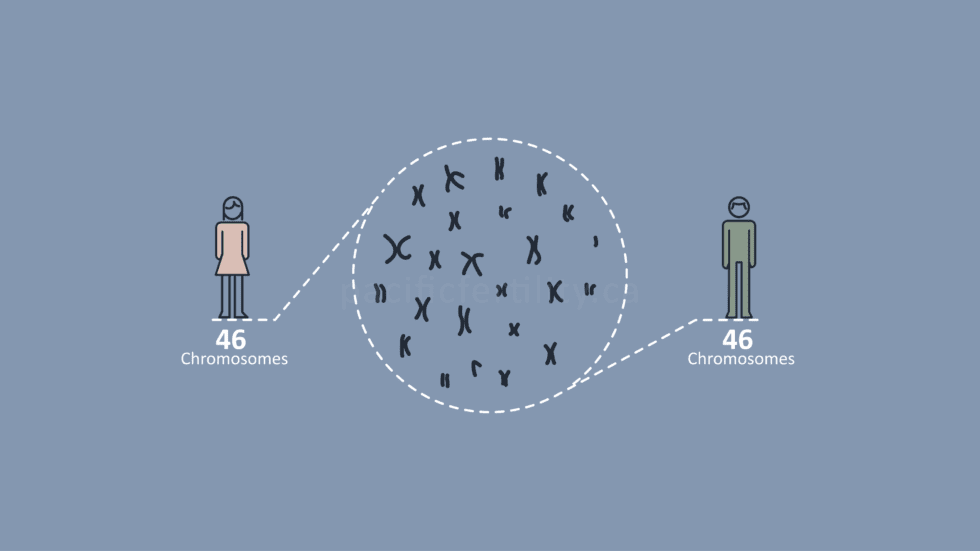

The most common genetic disorders are not those of single genes (ex. muscular dystrophy, Tay-Sachs disease, cystic fibrosis) but rather imbalances of the major pieces of material which hold genes, known as chromosomes. Chromosome imbalances in the egg or sperm result in an embryo with an extra chromosome. This condition is called trisomy. In the vast majority of cases trisomy occurs sporadically and is not inherited. The incidence of trisomy is associated with maternal age, and the chance of trisomy increases with a woman’s age.

The most common form of trisomy is Down syndrome (trisomy 21), which occurs when a person has an extra copy of chromosome 21. Infants with Down syndrome are developmentally delayed and have a higher chance of physical problems, including heart defects. The effect of trisomy 21 varies from mild to severe.

Trisomy 18 and trisomy 13 can also be observed in on-going pregnancies. Trisomy 18 and 13 are more severe than Down syndrome and are often considered lethal conditions. If a baby with trisomy 18 or 13 survive to delivery and are born living, they tend not to survive very long.

Screening for chromosome problems has changed over the past 15 years. Initially, a woman’s age was used to determine who was offered diagnostic testing by either amniocentesis or chorionic villous sampling (CVS). However, more accurate screening is now available by assessing specific ultrasound markers and the levels of certain proteins produced by the baby and placenta. Serum Integrated Prenatal Screening (SIPS), Integrated Prenatal Screening (IPS), Quadruple screening, First Trimester Screening (FTS), and Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) are all prenatal genetic screening options available in BC.

Birth Defects

Isolated birth defects are unlikely in the general population. Problems such heart defects, spinal defects, and facial defects are best seen at the anatomic ultrasound at 18-20 weeks of pregnancy. In the first trimester, we look at all possible anatomy that is visible, to determine problems early if they are present.

Spinal cord defects or open neural tube defects (ONTDs) are rare in the general population, affecting 1 baby in every 1,000. However, screening for these problems is relatively simple. A blood screen at 16-18 weeks called MS-AFP can detect about 70-80% of affected pregnancies. AFP is a part of Quad screening, SIPS, and IPS. More effective than MS-AFP is the standard detailed ultrasound at 18-20 weeks. This ultrasound is essentially diagnostic in the detection of ONTDs.

Placental Disorders

Over the last decade, medical research has shown that placental dysfunction can cause severe fetal-maternal complications such as fetal growth restriction and maternal hypertension. One of the elements of FTS risk assessment is the measurement of PAPP-A, a protein made by the placenta.

When there are problems with the placenta, the amount of PAPP-A may be lower than expected. Even if the baby’s trisomy risk assessment is normal, low PAPP-A is used as a marker for complications later in pregnancy.

Related Posts

Categories

About the PCRM Blog

Welcome to the Pacific Fertility Centre for Reproductive Medicine Blog! Nationally and internationally recognized for providing exceptional reproductive care, our team believes in empowering people with the knowledge they need to navigate their unique fertility journeys.

From information on the latest fertility treatments to valuable insights on egg donation, surrogacy, and everything in between, the Pacific Centre for Reproductive Medicine Blog is your ultimate resource for all things reproductive care and support. Read on to learn more, and contact us today if you have any questions or want to schedule a new patient appointment.